- March 23, 2023

Does cross subsidisation in group insurance lead to fair and economically beneficial outcomes for customers *

Executive Summary

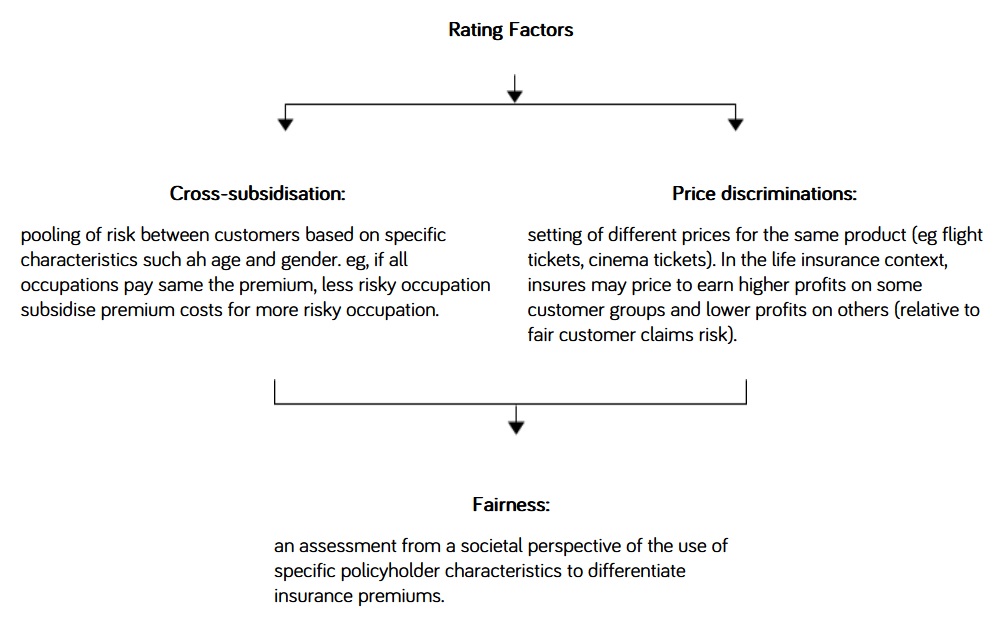

This research paper examines sources of cross-subsidies in group insurance and seeks to determine whether such cross-subsidies are fair and lead to economically beneficial outcomes. In order to answer this question we assessed some research frameworks that consider whether price discrimination and cross-subsidies are fair for consumers.

After reviewing the fairness of cross-subsidies framework from an Actuarial paper ‘The Discriminating Pricing Actuary’, we concluded that occupation would likely be societally deemed as the ‘most acceptable’ factor for use as a rating factor when calculating insurance premiums. Surprisingly the research framework would suggest that gender would be societally deemed a ‘less acceptable’ factor, because customers have no control over their birth gender, which biologically does not change over their lifetime.

Secondly, using a framework from the UK Financial Complaints Authority, principles of fairness were outlined in their paper titled “Price discrimination in financial services”. We applied this framework to the insurance in superannuation context, suggesting that societally it would be viewed as unfair if younger members subsidise other insurance members, and also that it would be viewed as unfair for female members to subsidise male members.

Finally, we reviewed Legislative and Regulatory guidance to summarise the responsibilities that apply to Trustees for managing cross-subsidies. Generally, this review found that there are not many regulations or laws that require Trustees to avoid cross-subsidies within insurance premiums.

Context

Historically, group insurance pricing focused on the principle of mutuality and the cost of insurance was identical for all members. The sum insured scale may have included some age differentiation but there were unrealised cross-subsidies embedded within the design across age / gender / occupation. Over time, an emphasis on fairness led to tailored group insurance pricing, with some schemes varying their pricing based on factors including age, gender and , occupation and sometimes the category or division (such as Retained Division member).

Group insurance product design can vary significantly by scheme and consequently the level of cross-subsidies will vary by exist in some scheme but not others. Recent PYS and PMIF legislation led to industry wide premium increases for insurance in superannuation, partially because it was recognised that younger ages were cross-subsidising older ages at the industry level. The question needs to be asked: is it fair for younger ages to subsidise older ages? What about other sources of cross-subsidisation?

Purpose

This research paper will examine sources of cross-subsidies in group insurance and ask whether the cross-subsidies are fair and lead to economically beneficial outcomes, by applying select frameworks from research papers: The Discriminating (Pricing) Actuary ¹ and Price Discrimination in Financial Services – how should we deal with questions of fairness? ²

1. “Fairness” of cross-subsidisation in group insurance

At the core of insurance is the pooling of risks across a group of individuals. In the current group insurance context, for insurance in superannuation – the trustee makes the final decision on whether cross-subsidies should exist for any combination of age, gender or occupation* *. The trustee will also have discretion to choose the benefit design and may also choose to price discriminate between any of the above factors.

* * with reliance on recommendations from life insurers and other advisers, noting that cross-subsidies are sometimes not actively chosen, are may not be discovered or are implicit in premium rates.

The following frameworks will be applied to assess whether the use of certain factors is “fair”:

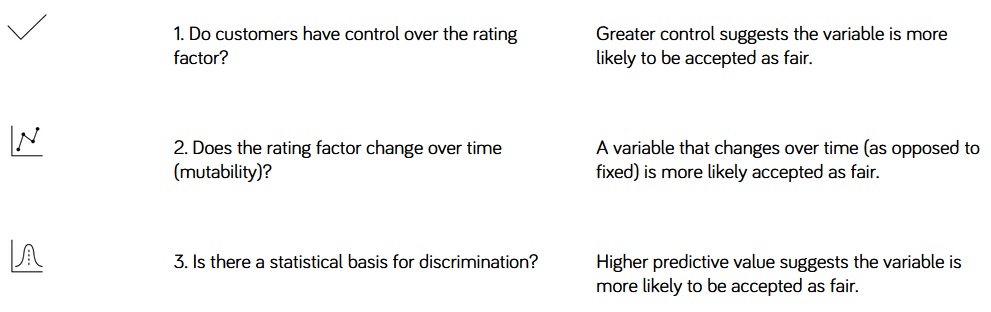

Framework A. Hygiene criteria to assess the possible use of rating factors

Framework B. Procedural fairness

Framework C. Distributive fairness

Framework A. Hygiene criteria to assess the possible use of rating factors for life insurance products ³:

| Control | Mutability | Statistical discrimination | Hygiene criteria ( Total rating ) |

Age | No control (-) | Changes (+) | Predictive value (+) | Acceptable |

Gender | No control (-) | Doesn’t change (-) | Predictive value (+) | Less Acceptable |

Occupation | Control (+) | Can change (+) | Predictive value (+) | Most acceptable |

Note: for illustrative purposes only, not comprehensive. Postcode is not typically used as a rating factor, but is included here for argumentative purposes.

Based on the framework and factors examined above, occupation would be the ‘most acceptable’ factor for use as a rating factor when calculating insurance premiums, satisfying the control and mutability tests. Gender would be a ‘less acceptable’ factor, where customers have no control over their birth gender, which biologically does not change over their lifetime. Postcode has similar characteristics to occupation.

Most factors above are statistically credible factors, which may itself be sufficient to allow use as a rating factor. For example, while Gender is classified as being ‘least acceptable’, it is accepted in Australia as a rating factor (though not in all regions such as Europe ⁴).

The framework is a screening test for to assess the use of rating factors by life insurers. Additional questions and factors below need to be asked to assess the appropriateness of using each factor from a social perspective.

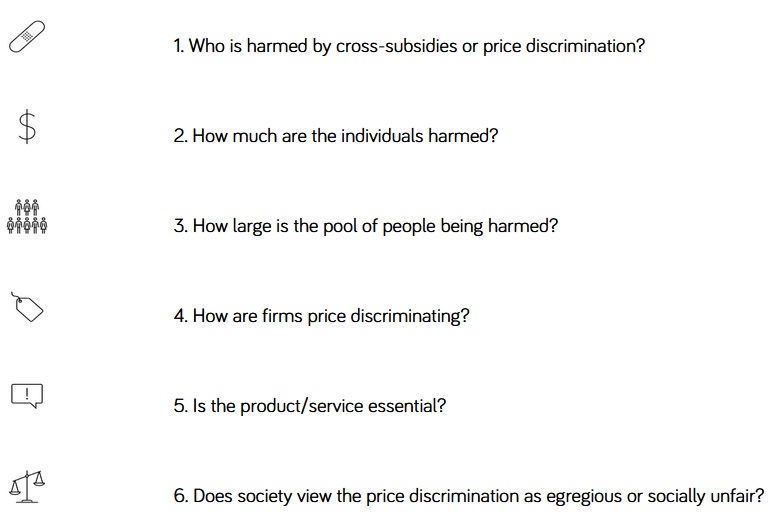

Framework B. Distributive fairness: how are different groups of customers harmed by cross-subsidisation or price discrimination activity and is this acceptable from a social viewpoint? ⁵

Framework B reviews Distributive Fairness through guidelines established by the UK Financial Complaints Authority.

Questions examined are:

| Age | Gender | Occupation Rating | Postcode (illustrative) |

1. Who is harmed? | Younger ages – less risk of claiming relative to older ages | Females for group life – lower mortality Males for income protection – lower incidence | Less risky occupations. If those occupations are subsidising some of the higher risk or hazardous occupations. | Lower socio-economic status may have. |

2. Degree of harm | Varies depending on extent of price discrimination | |||

3. Size of pool harmed (Large) | Minority (eg ages <30) | By super balance (male/female): 61.2%/38.8% (approx. 50/50 by account number)⁶ | Varies by industry and employer | Varies |

4. Method of discrimination | Hidden premium discrimination that is invisible to customers. Using an economic analogy, customers are ‘price takers’ and price competition does not exist at the customer level (only at the aggregate level during the group insurance tender process) | |||

5. Essential product or service? | Group insurance is highly desirable as a mechanism to provide a basic level of life insurance cover to society | |||

6. Society’s view on fairness | Unfair – fairness in shift of insurance costs from younger to older members | Unfair – contributes to gap between gender super balances at retirement | Acceptable – promotes access to life insurance for risky occupations | Unfair – would tend to increase the income and wealth inequality divide. |

Further commentary:

Age: recent PYS and PMIF legislation was implemented due to the ‘poor value’ of insurance provided to young members according to the Productivity Commission ⁷. The removal of life insurance would effectively increase super balances for young members by the premium cost. With increased focus on value, it would appear contradictory for young members to cross-subsidise older ages. The opposing view would recommend that younger ages be cross-subsidised, to encourage insurance take-up among younger members.

Gender: the removal of a gender rating may have unequal impacts on members within a scheme. Females would subsidise males for group life products; males would subsidise females for income protection products.

It would be financially advantageous for females to pay lower premiums for group life cover where gender rating is in place.

While the existing super balance gap favours males, the gap will likely self-correct, as an increasing proportion of females participate in the workplace over time ⁸ and future initiatives are implemented to promote the female participation rate.

Occupation rating: group insurance is a means for those in more risky occupations to purchase a basic level of insurance at a more affordable premium relative to retail insurance. However, certain special risk occupations may face additional loadings and/or exclusions, to limit the impact on improve affordability for those in less risky occupations.

Postcode: could be societally unwelcome ~ the use of postcode as a proxy for socio-economic status could increase the income and wealth inequality divide.

The social viewpoint is not static and evolves over time. Current topical issues shaping fairness in cross-subsidisation or price discrimination include lack of engagement with insurance in super (particularly in younger members), intergenerational wealth transfer and gender equality. In reality, there is sometimes a disconnect between social views on fairness and existing product design.

2. Trustee and Insurer responsibility for members’ insurance in super relating to cross subsidies and price discrimination

Current duties and obligations of trustees are sourced from a variety of areas, ranging in degree to which they are binding and the specificity of each. An analysis of existing trustee duties and obligations will be conducted with specific reference to price discrimination and cross-subsidies.

Select sections relating to the evaluation of insurance needs across a membership profile:

Source | Section | Description |

SPG250 (a guide to SPS250)⁹ | SPG250: 25 – 27 | Source : 26. “Evaluate all the elements of the insurance covenants and to be able to demonstrate how each of the elements impact on the overall outcomes achieved for members. For example, … demographic composition and risk profile, the likelihood of these members needing to claim, and the comparative impact on these members of having a different level and/or type of insurance cover”. Commentary : While the demographics of members needs to be considered, there are no wider provisions focused on cross-subsidies or the relationship between underlying risk and premium cost. Source : 27a. Consideration of “…which beneficiaries are to be provided with insured benefits and at what level, including when insured benefits of a particular type are not appropriate to make available to some groups of members or beneficiaries (e.g. when the best interests of casual employees and beneficiaries close to retirement age may not be served by these types of benefits)”

Commentary : While there may be consideration of the above, what does the spectrum of acceptable designs look like? Should there be greater guidance on best practice? In the current environment, two funds with similar membership profiles may have widely ranging product designs. |

Insurance in Super Voluntary Code of Practice | Benefit design 4.5 | Source: “When we design insurance benefits, we will assess our members’ likely insurance needs, including considering the following characteristics of our membership…[including] a) age distribution b) gender c) industry and occupation…” Commentary : Similar with the point above, what constitutes a valid and thorough assessment? Should an assessment include a review of cross-subsidies and price discrimination? This comment only pertains to insurance benefit design, and not the aspects relating to the pricing of the cover. |

A greater focus on cross subsidies may lead improved outcomes for superannuation account balances. In a consultation response from the Actuaries Institute regarding PYS ¹⁰, a recommendation is made such that SPS/SPG250 and LPS270 (Group Insurance) be amended to include additional obligations for trustees/insurers in relation to cross-subsidies as a means to reduce account balance erosion.

Given the uniqueness of membership profiles, what degree of intervention might be required to restrict or allow cross-subsidies? The following questions could be considered ¹¹:

Question | Discussion |

Would increased trustee duties be proportionate in terms of costs and benefits? Could a desired outcome be achieved by less intrusive measures? | Most efficient method of implementation would be through voluntary codes of practice, which has lower priority relative to prudential regulations. |

What is the impact of intervention on competition, average prices and particular groups of consumers (especially vulnerable customers)? | Reduxtion of cross-subsidies would ‘rebalance’ premiums across policyholder groups. Trustees would be required to actively consider cross-subsidies. |

Could there be negative unintended consequences? | Over-regulation could restrict the degree of autonomy over product design. Member groups are inherently different and some might have specific requirements. |

Outside of a regulatory approach, improved awareness of cross-subsidies and increased communication will lead to better outcomes for customers through product design and pricing. Life insurers need to be more pro-active with highlighting the cross-subsidies that exist as a result from specific product design.

Trustees are encouraged to probe into the cross-subsidies that exist in current product designs to consider whether they are desirable and appropriate for the membership profile. Emphasis should be given to cross-subsidies that impact age (consistency with the purpose of PYS/PMIF) and other factors that satisfy the ‘unfairness’ tests. Whilst this may be a difficult exercise, it is a consideration often overlooked.

Conclusion

Looking into the future in the superannuation industry, fund merger activity is becoming increasingly likely, suggesting greater pooling of members with diverse characteristics. As such, it is becoming even more important that cross-subsidies be reviewed, particularly as part of the product design review process. Recent industry wide premium increases in group insurance following PYS/PMIF is a reminder that much work is required to unravel the implications of cross-subsidies, requiring both the trustee and life insurer to work closely together.

References

¹ Edward W. (Jed) Frees University of Wisconsin – Madison, Australian National University, Fei Huang, University of New South Wales

² Financial Conduct Authority (UK)

³ The Discriminating Pricing Actuary, referencing Avraham (2018), Prince and Schwarcz (2020)

⁴ EU Charter of Fundamental Rights, https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/MEMO_12_1012

⁵ Price Discrimination in Financial Services – how should we deal with questions of fairness? UK FCA

⁶ https://www.superannuation.asn.au/ArticleDocuments/359/1710_Superannuation_account_balances_by_age_and_gender.pdf.aspx?Embed=Y

⁷ PC, Superannuation: assessing efficiency and competitiveness, Inquiry report, op. cit., p. 41, (recommendation 15), cited in https://www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Bills_Legislation/bd/bd1920a/20bd032#_Toc19599455

⁸ https://treasury.gov.au/sites/default/files/2021-04/p2021-164860_australian_labour_force_participation.pdf

⁹ Based on proposed revisions to SPS250 and SPG250, as at January 2021, sourced from APRA.

¹⁰ https://actuaries.asn.au/Library/Submissions/FinancialServicesReform/2018/20180529SubTreasConsult.pdf

¹¹ Price Discrimination in Financial Services – how should we deal with questions of fairness? UK FCA